Iceland–An Independent People

April 20, 2011 at 2:49 pm | Posted in democracy, Free Trade, International Relations, Labor, Political Economy, World Politics | 2 CommentsTags: 21st Century Capitalism, Euro, European Union, financial crisis, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Internnational Monetary Fund, Ireland, Libya, NATO, neo-liberalism, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, United Kingdom, US hegemony, US politics, World-economy

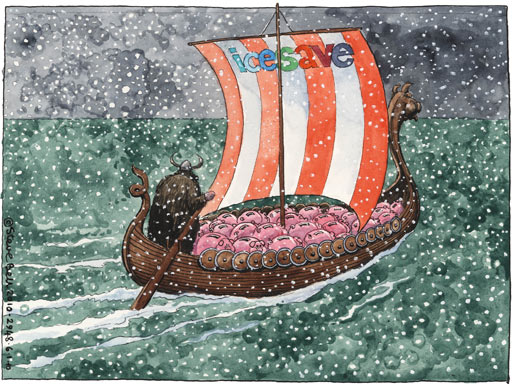

In the midst of the NATO campaign against Libya and the budget deal between Republicans and the Democrats in the US, a far more historically significant event appears to have fallen off the radar. On April 9, 2011, the people of Iceland voted for the second time to reject a government proposal for Iceland taxpayers to repay some €4 billion to the governments of Britain and the Netherlands which had compensated their domestic depositors in the collapsed online bank, Icesave. Initially, the British and Dutch governments had pressured the Iceland government to agree to repay them over fifteen years at a 5.5 percent annual interest–which was estimated to cost each household in the tiny island nation about €45,000 over the period. This was rejected by 91 percent of the voters in a referendum in March 2010. After subsequent negotiations, London and Amesterdam agreed to lower the interest to 3.2 percent and stretch the repayment period to 30 years between 2016 and 2046. The deal was accepted by a large majority of 44 in favor and 16 opposed in the Althingi, Iceland’s parliament, which also rejected a clause to submit the bill to another referendum. Nevertheless, as the President, Olafur Ragnar Grimsson, refused to sign the bill, it was automatically subject to a referendum wherein it was rejected by almost 60 percent of the voters.

The Dutch and British governments–which had used anti-terrorist legislation to seize assets of the failed Icelandic banks–have threatened to scupper Iceland’s application to join the European Union and to take the island nation to court. Reykjavik has insisted that the two governments would get most of their money back and the assets of the Landsbanki bank which set up the Icesave operation would be sold and was expected to realize 90 percent of the Icesave debt. What was at issue in the referendum was not whether London and Amsterdam would be compensated or not–but whether private citizens should be expected to shoulder the burden of repayment of a bank’s debt in which they had no hand in incurring and from which they did not benefit. The threat to take Iceland to court is important because it is to frighten off other states which also face indebtedness due to the financial crisis like Greece, Ireland, and Portugal. It is simply the question of whether the bankers have to bear the burden of the bad loans they have extended.

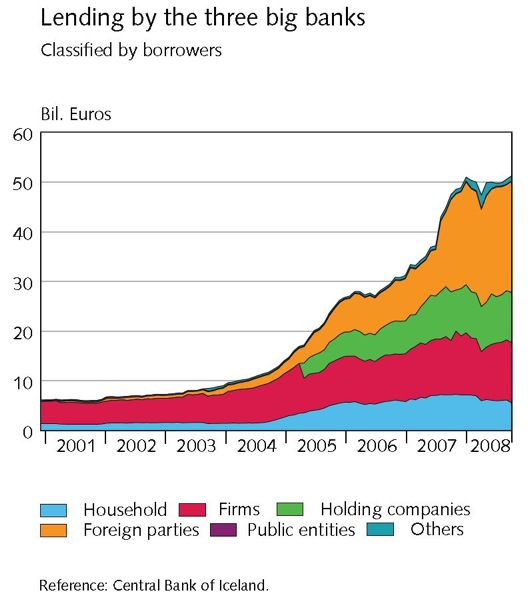

Iceland is, in fact, a case study of neo-liberalism gone awry. Before the late 1990s, Iceland’s financial sector had been small and the banks were largely government-owned. In 1998, the two leading parties–the Independence Party and the Centre Party–embarked on a privatization of the banking sector, assigning Landsbanki to grandees of the Independence Party and Kaupthing to the Centre Party. A new private bank, Glitnir, was also set up merging several smaller banks. None of these banks had much experience in international finance, but like South Korean banks a decade earlier, these banks tapped into abundant cheap credit and easy capital mobility. Unlike the South Korean banks, their strong ties to political parties, the merger of commercial and investment banking, and low soveriegn debt meant that they got extremely high grades from the credit ratings agencies and as Robert Wade and Silla Sigurgeirsdottir note: “government policy was now subordinated to their ends.”

With the government relaxing mortgage rules to permit loans up to 90 percent of value, the banks rode the wave–by buying shares in each other they inflated share prices and enticed depositors to shift their savings to shares. In less than 10 years after the privatization of banks, Iceland had the fifth highest GDP in the world, 60 percent higher than that of the United States, and the assets of their banks was valued at 800 percent of Iceland’s GDP. As land prices soared, Icelanders loaded up on lower-interest yen- or Swiss-franc debt.

By 2006, Iceland’s current account deficit had soared to 20 percent of its GDP. Late in that year, Landsbanki established an online bank, Icesave, to attract deposits from overseas clients and by offering highly attractive interest rates, it raked in millions of pounds from England, and later millions of euros especially from the Netherlands. This was soon copied by the two other banks. These were established as ‘branches’ rather than as ‘subsidiaries‘ which meant that they were to be supervised by the icelandic Central Bank rather than regulators in Britain or the Netherlands. Because of Iceland’s obligations as a member of the European Economic Area to insure bank deposits, no one thought to worry about whether the Icelandic Central Bank had the capacity to oversee the vastly extended operations of the island’s three major banks.

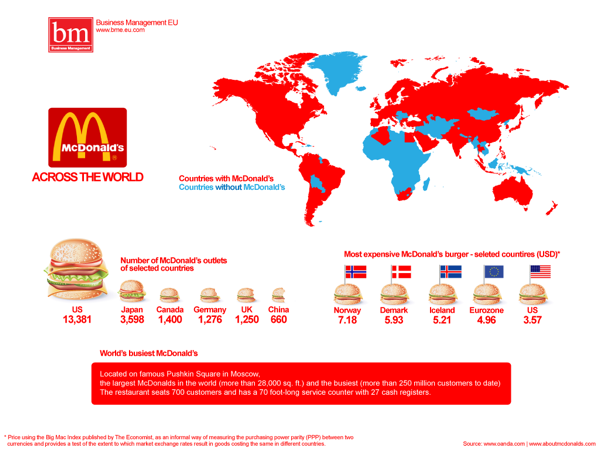

This happy bubble burst in September 2008 when Lehman Brothers collapsed, within a fortnight of which the three big Icelandic banks collapsed and by November of that year the krona had fallen from its pre-crisis level of 70 to the euro to 190 to the euro, so sharply cutting the islanders’ purchasing power that the three McDonald’s franchises were forced to close as the cost of importing ingredients made the price of burgers prohibitive! The country’s stock market lost 98 percent of its value! If ever there was a definition of crisis, this was it. It was the first time in over 30 years that a ‘developed’ state had to seek assistance from the International Monetary Fund.

In the light of all this, Iceland’s voters have had the courage to face up to the crisis. It was the first country to kick out the government which had failed so spectacularly. Unlike its neighbor in the North Atlantic–Ireland which underwrote its own banking collapse and loader every household with €80,000 in debt–Iceland let the three banks go under and they imposed capital controls to prevent the flight of capital. Though unemployment in Iceland today is 7.5 percent in Iceland–up from 2 percent in 2002–but just over half of Ireland’s 13.6 percent. Though the krona lost almost half its value, inflation is down sharply and without having to pay back foreign creditors, its government finances are in much better shape than those of Greece, Ireland, or Portugal.

Eurozone’s Woes

December 4, 2010 at 5:47 pm | Posted in International Relations, Political Economy, world politics | Leave a commentTags: 21st Century Capitalism, Euro, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Kazakstan, Portugal, Spain, world politics, World-economy

The Euro–the single currency adopted by 16 states–has been under siege for over a year beginning with the election of a new government in Greece in September 2009 which sharply revised the country’s public deficit from 6 percent of GDP to 12.7 percent. This led to a loss of confidence in the government’s ability to repay loans and raised the cost of borrowing, creating greater difficulties for the government to repay the 300 billion euro debt bequeathed to it by its predecessor in office. Normally, a government faced with high debts could devalue its currency and thereby increase the competitiveness of its exports and attract both foreign investments and tourists but the adoption of the common currency ruled out this option.

Eventually, the European Central Bank (ECB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) cobbled together a rescue package of €110 billion ($146 billion) in May 2010 in return for Greece implementing very severe austerity measures. European policy makers also set up a European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) to create a safety net of upto €750 billion to preserve financial stability among member states of the common currency.

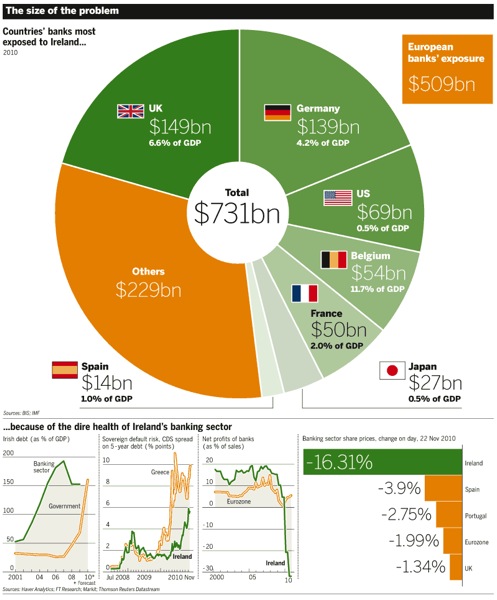

These floodgates came under renewed threat when German Chancellor Angela Merkel made a statement that in future financial crises, creditors must also share in the losses rather than only the tax-payers. As Ireland was the most indebted economy within the Eurozone, this caused interest rates on Irish bonds to spike causing a further crisis in confidence. Unlike the Greek crisis which was caused by high public deficits, the Irish crisis was caused by a collapse of its housing bubble.

Soon after the introduction of the single currency, weak economic demand in the main Eurozone economies–Germany’s real domestic demand in 2008 was only 5 percent higher than in 1999–fueled an asset price inflation-especially in Ireland and Spain. As the former taoiseach (Prime Minister) Garret Fitzgerald noted, the house construction rate in the Celtic Tiger in the last two decades was six times that of Britain–leading to an extraordinary housing bubble stimulated by the Anglo Irish bank and a host of overseas banks. When the bubble burst, instead of the banks’ creditors sharing the losses, the government assumed their payment obligations, nationalizing the Anglo-irish Bank and creating the National Asset Management Agency to take over large loans from other banks, effectively transforming private debt into public debt.

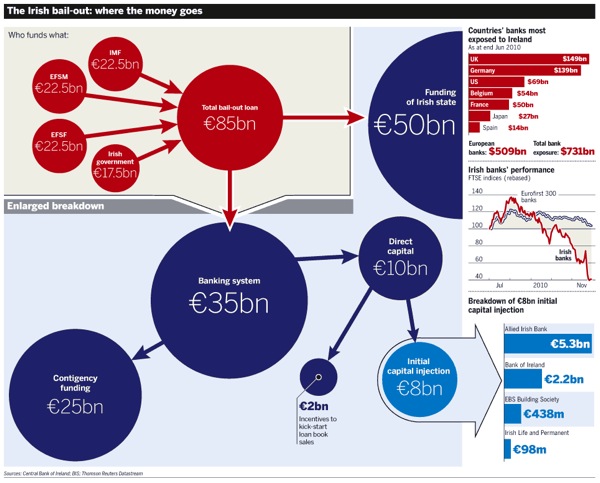

The ECB and IMF have once again cobbled together a rescue package of €85 billion ($115 billion) but this has not stopped a massive gap in the bond spreads (an increase in the cost of borrowing for the weaker members of the Eurozone, especially Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain, and Italy) and the fear is that if the crisis spreads to Spain and Italy, two of the largest economies, the EFSF would be inadequate and it would cause an enormous political conundrum: citizens of the stronger states will become increasingly unwilling to bail out the more ‘profligate’ states, and citizens of the latter would be unwilling to put up with increasingly stringent long-term austerity measures.

Spain is fortunate because a large amount of its government debt is owed to its own banks rather than to overseas banks. At the beginning of 2010, Spain’s public debt was only 53 percent of GDP, about 20 percentage points below that of the Eurozone average and half that of Italy’s. Last year, when the budget deficit stood at 11.1 percent of GDP, Prime Minister Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero also pushed through an austerity package that led to the government’s deficit falling by 47 percent in the first ten months of 2010. The problem for Spain is its high private debt–especially the heavy borrowing from overseas banks to fund home construction in the years up to 2008, Before the start of the recession, Gilles Moec of the Deutsche Bank estimated that private sector debt was 210 percent of GDP compared to 130 percent for Germany, France, and Italy.

If the extent of the impending crisis have left many to wonder about the future of the euro, the problem surely is not in the common currency. As Philippe Legrain wrote in the Financial Times there is a lot to be said for

What was the problem was that capital from the stronger members of the Eurozone was channeled to fund asset bubbles in Ireland, Spain, and elsewhere. Tighter regulations of cross-border investments can mitigate this problem. But more importantly, why are lenders coddled in cotton wool while taxpayers are burdened with huge debts they had done nothing to incur? Ordinary Irish citizens, as Paul Krugman, has underlined are:

bearing a burden much larger than the debt — because those spending cuts have caused a severe recession so that in addition to taking on the banks’ debts, the Irish are suffering from plunging incomes and high unemployment.

Earlier when Iceland and Kazakhstan faced financial crises, creditors shared in the pain. The external debt of Kazakhstan’s banking sector which had stood at 26 percent of GDP when the crisis struck in February 2009 had been cut almost in half by September 2010 by making creditors share in the losses and accepting various combinations of senior and subordinated debt. There is no reason to let banks off the hook. In Iceland, the crisis caused the election of a left-leaning government which also were able to get better terms.

If the current crisis enveloping the Eurozone leads to the election of more left leaning governments, and to a refusal to nationalize private debt and to greater regulations over the economy, it may be the final nail in the neoliberal coffin!

Create a free website or blog at WordPress.com.

Entries and comments feeds.