A Fog of Myths About North Korea

April 29, 2013 at 1:59 pm | Posted in Arms Control, Capitalism, Human Rights, International Relations, Nuclear Non-Proliferation, Political Economy, World Politics | Leave a commentTags: China, East Asia, India, interstate system, Israel, Japan, North Korea, Pakistan, South Korea, the Philippines, United Nations, United States, US hegemony, Vietnam

Rarely has the manufacturing of consent in the mainstream media been as thorough as it has been in the case of North Korea. It is the original ‘hermit kingdom,’ isolated from the outside world by a dynasty of communist dictators–a ‘socialism in one family’–and irrational to the extent of threatening Washington with a nuclear Armageddon. This reigning consensus is so widespread that there has been little challenge to it in the major news outlets of the world and yet, a moment’s reflection suggests that there are many flaws in this narrative.

In the first instance, in a rare piece of insight into North Korea, a former Western intelligence officer who writes under the pseudonym of James Church has argued that since isolationism is a two-way street, the rest of the world is even more ignorant about North Korea than Pyongyang is about the wider world. After all, North Korean officials can monitor radio and television broadcasts, plug into the Internet, and analyse books and magazines from the outside world. They know what people outside their borders are thinking and doing. But people outside North Korea have little insight into what goes on in the country and are metaphorically reduced to examining the entrails of sacrificial animals to divine Pyongyang’s intentions.

Hence, Church writes, “We…have developed a fog of myths about them as a substitute for knowledge. These myths, handed down from administration to administration, are comforting in their long familiar ring, but make it difficult for us to avoid walking in circles. The North Koreans move nimbly through this fog” like small boats deftly weaving in and out between lumbering vessels.

Rather than nuclear weapons, Church argues, North Korea’s greatest strength is the capacity to behave badly: by carefully choosing the right time, it knows its actions will force big powers to pay close attention even though they may grind their teeth. What it fears most is being swept aside in big power politics, so by playing its weak hand cleverly, it seeks dialogue with the United States, a process that was derailed when former president George W. Bush labelled it part of an “axis of evil.”

Recent concerns about Pyongyang’s nuclear program stemmed from an underground nuclear test on February 12, 2013—its third in seven years. In response, the United States and its allies pressed the UN Security Council to add new sanctions on the country: enhanced scrutiny over shipments and air cargo, a ban on the sale of luxury goods, expanded restrictions on a range of institutions and senior officials. China, notably, signed on to these sanctions and did not veto them.

If China is dragging its feet on the issue of North Korea, it is also because Beijing has a stake in the survival of the Kim Jong-eun regime. The collapse of North Korea could bring a stream of refugees to China which already has 2 million ethnic Koreans and threaten the stability of the border region. Moreover, since a unified Korea is likely to be led by Seoul, it raises the possibility of US forces on China’s border with Korea. A unified Korea with some 70 million people would also become a formidable economic competitor and transform the dynamics of the regional economy as Timothy Beardson writes in the Financial Times.

When President Barack Obama acknowledges that North Korea does not have a single deployable nuclear warhead, and according to SIPRI, the five permanent members of the Security Council—all declared nuclear powers—had approximately 19,265 as of January 1, 2012, this response to Pyongyang’s third nuclear test seems disproportionate. This is all the more so since North Korea has withdrawn from the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and the other states outside the NPT—India, Israel, and Pakistan—are not treated in the same way as Pyongyang. As Jonathan Steele writes in the Guardian, “If it is offensive for North Korea to talk of launching a nuclear strike against the United States (a threat that is empty because the country has no system to deliver the few nuclear weapons it has), how is it less offensive for the US to warn Iran that it will be bombed if it fails to stop its nuclear research?”

In response, statements in the official newspaper of the ruling Workers’ Party of Korea (WPK), Rodong Simun, on March 6, 2013 declared that if the US continues to threaten it with nuclear weapons, Pyongyang now had the ability to turn Seoul and Washington into “a sea of fire.” North Korea also repudiated the 1953 Korean War ceasefire and cut the Red Cross hotline though lines between military and aviation authorities across the 38th parallel remain open.

Notably, till the middle of March, its foreign office maintained that it will abandon its nuclear weapons program if the United States removes its nuclear threats and abandons its hostile posture.

In reply, as Peter Hayes and Roger Cavazos of San Francisco’s Nautilus Institute note, on March 25 the United States flew B-52 Stratofortress stealth bombers over South Korea in military exercises that stimulated a nuclear attack on North Korea. Not only did these military exercises stir deep memories in North Korea where air raids killed an estimated 20 per cent of the population during the Korean War but the B-52 flights at the same time demonstrated China’s inability to affect US mobilization. The United States also bolstered its anti-missile batteries in Alaska and the West Coast.

Should it then surprise us that the North Korean ruling party’s Central Committee Plenum meeting set a ‘new strategic line’ of simultaneously pursuing the path of economic construction and “building nuclear armed forces”? It also announced that it would resume uranium enrichment at the Yongbyon reactor plant that had been moth-balled in October 2007 as a part of the denuclearization process.

Nevertheless, the WPK’s Central Committee Plenum ended by also declaring that “As a responsible nuclear weapons state, the DPRK [Democratic People’s Republic of Korea] will make positive efforts to prevent the nuclear proliferation, ensure peace and security in Asia and the rest of the world and realize the denuclearization of the world.”

In a state born of guerrilla struggle, leadership requires as Hayes and Cavazos suggest, endless battles and if Kim’s leadership itself is not under threat, he needs to embellish his own credentials. Hence, his belligerence is intended as a professor of Sociology at Seoul National University also suggests, as a manoeuvre to outflank the military while preparing the ground to initiate a more pragmatic economic policy. Thus amid the rattling of nuclear sabres, Kim has appointed as his premier, Pak Pong-ju a pragmatic economist who had been forced out of office in 2007 by the military, reportedly because he followed Chinese suggestions on economic reforms too closely.

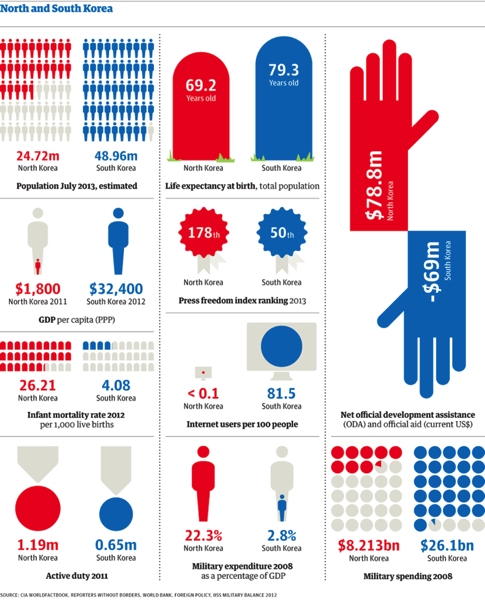

North Korea does not have enough resources to build its economy and to maintain the world’s third largest conventional armed force. Unlike China when it started its reform process in the late 1970s, Pyongyang does not have a huge reserve labor force in agriculture. Its economy is sustained only by extensive food and oil imports from China. To successfully pursue economic growth, a nuclear deterrent will enable Kim to divert labor from his conventional military and hence the ‘new strategic line’ announced by the WPK’s Central Committee Plenum—to simultaneously work at both economic construction and ‘building nuclear armed forces.’

However, by promising not to export nuclear weapons or material, Kim signals that he has no intention of crossing red lines. Indeed, during the recent visit to North Korea by US basketball star Denis Rodman, Kim asked him to tell President Obama to phone him. The American president pointedly refused to accept this invitation in an interview with George Stephanopoulos.

Again, in an unusual move, North Korea’s ambassador to the United Kingdom, Hyon Hak-bong addressed the Communist Party of Great Britain (Marxist-Leninist) and asserted that North Korea’s only interest was its legitimate self-defence. While North Korean ambassadors have attended meetings of fraternal associations in the past, it has usually been to accept messages of appreciation or praise—not usually to make statements. What better way to signal Pyongyang’s intentions to negotiate than for its ambassador to make a statement in a European capital?

All US Secretary of State, John Kerry, would offer in return was an offer to talk if North Korea offered unspecified concessions to show its good faith. Faced with US and South Korean intransigence, North Korea effectively closed the Kaesŏng Indusrial Park—a special industrial region—where 123 South Korean companies had been employing 53,000 North Korean workers and directly paying Pyongyang $90 million in wages every year. Significantly, while this is a serious loss to the Kim regime, it is also a non-military response to what the regime sees as persistent US provocation.

While the military was suspicious of Kaesŏng, viewing it as a Trojan horse, the regime’s decision to close it (perhaps temporarily) may indicate that it is trying to show that it is willing to bear a significant cost to send a message that it is serious in its stance.

This should be seen in the light of the fact that the government has turned a blind eye to the growth of a market activities in the country which, Andrei Lankov, a Russian specialist on Korea estimates provides 75 per cent of the income of the people outside the military and the upper echelons of the party. Frequent travel to China and the availability of DVDs about South Korea have opened their eyes to new possibilities offered by consumerism.

This makes it all the more important for the regime to compel its adversaries to change their policies, to secure a peace agreement, to denuclearize the peninsula, and to get reparations from the Japanese who colonized the country from 1895 to 1945. This has been the aim of the regime for 60 years but has assumed a new urgency. A peace treaty is a sign that Pyongyang needs to show that the United States and its friends that grotesquely masquerade as “the international community” accepts it as a legitimate state.

Create a free website or blog at WordPress.com.

Entries and comments feeds.